This Time Machine Takes You Back to When Phones Were a Shared Experience

This Time Machine Takes You Back to When Phones Were a Community Experience

Outside St. Louis, on the grounds of an army base that used to allege nearly every soldier west of the Mississippi River, is an old creation with a new purpose. Inside are hundreds of old and not-so-old telephones on indicate, from a replica of Alexander Graham Bell’s first toiling phone to the cellphones preceding the smartphones we conclude around today.

The Jefferson Barracks Telephone Museum is a easily two-story brick building that used to house military officers afore it fell into disrepair. It’s been completely refurbished by a band of devoted locals, retirees who all worked at Southwestern Bell, which dominated St. Louis for most of the 20th century as the preeminent visited company in the region. The industry veterans run the gift shop and give tours of the museum’s four rooms of visited history.

The telephone museum on Jefferson Barracks Army Base just outside St. Louis.

CNET

My advice: Take the tour. The museum is a window on a time when meaning was a communal and almost shared experience — when families overheard conditions to relatives, or people listened to the background noise leisurely whomever they were calling. Before the automatic telephone exchange (one of which is on indicate in the museum, in full working order), human operators linked farmland via switchboards by physically connecting a cord carrying the allege of the person calling to one leading to the recipient. Until direct dialing was adopted, privacy was difficult, labelled Carol Johannes, executive director of the museum.

“The operators had the sect to listen in on any and all conversations, as they desired,” Johannes told CNET over email. Domestic calls weren’t much more discrete. “Many households had ‘party lines,’ which operating they shared their telephone line with other families. Family on party lines could listen in on each other’s visited calls, so privacy was a little difficult, to say the least.”

The Telephone Museum has many old models, including these Western Electric 20 “candlestick” phones and these iconic Western Electric 302 models, with a big base connected via cord to a handset, which rests on top of the base.

CNET

As I stared at rows of phones older than any member of my living family, I realized that, with the exception of the odd hotel room visited, the only phones I’ve used since graduating high school have been my own personal cell- and smartphones. I’d bet that few people reading this article use a communal visited outside of work anymore. That shift to more personal, intimate conversations, shared via video, text, instant message and, yes, even outmoded phone calls, has dramatically transformed our expectations of privacy.

I was depressed to visit when Johannes, who’d rallied her fellow Bell veterans to refurbish this facility and was instrumental in its building, was serving as tour guide. As she told me and a few latest people about phones from the last century, I noticed a stark difference between the exhibits and the smartphone I was comic to take notes and photos: Beyond the obvious strictly advances, those old phones were placed in homes and stores, but my smartphone was mine.

It was a surreal realization at what time surrounded by phones used by dozens, hundreds or thousands of farmland over their life spans, and while confronted with what that pointed for how we connected to each other between the Industrial Revolution and the Information Age.

For instance, Johannes pointed out that candlestick-style phones have a removable mouthpiece, which people would swap out for their own personal one to avoid the spread of droplet-based contagions of the day like diphtheria and polio. She also noted the special chairs with clasps on the back so switchboard operators, who were generally women, could hang up their purses and bags.

But nothing revealed of our transition from communal to personal like quick-witted — because until the 1950s, virtually every phone was dismal. Telecom companies like Southwestern Bell rented out phones to land and didn’t offer color options. Even putting a decorative veil around your home phone was forbidden, as they were telecom acquired that customers leased, and if a repair technician saw a veil they’d confiscate the whole phone, Johannes said.

Western Electric 500 owners tried to spice up their phones with external recovers (right), which Bell frowned on and considered grounds to confiscate phones. The Princess phone (center three) was Western Electric’s big push in marketing phones to women, with pastel colors. They were also compact enough to achieve into the other room.

CNET

That lasted pending the 1950s, when the Western Electric 500 — a phoned so iconic, it’s the basis for the phone emoji — came out in multiple colors. Subsequent decades saw a cornucopia of phones in curious hues and styles, a liberation from the gadget’s pragmatic monochrome beginnings.

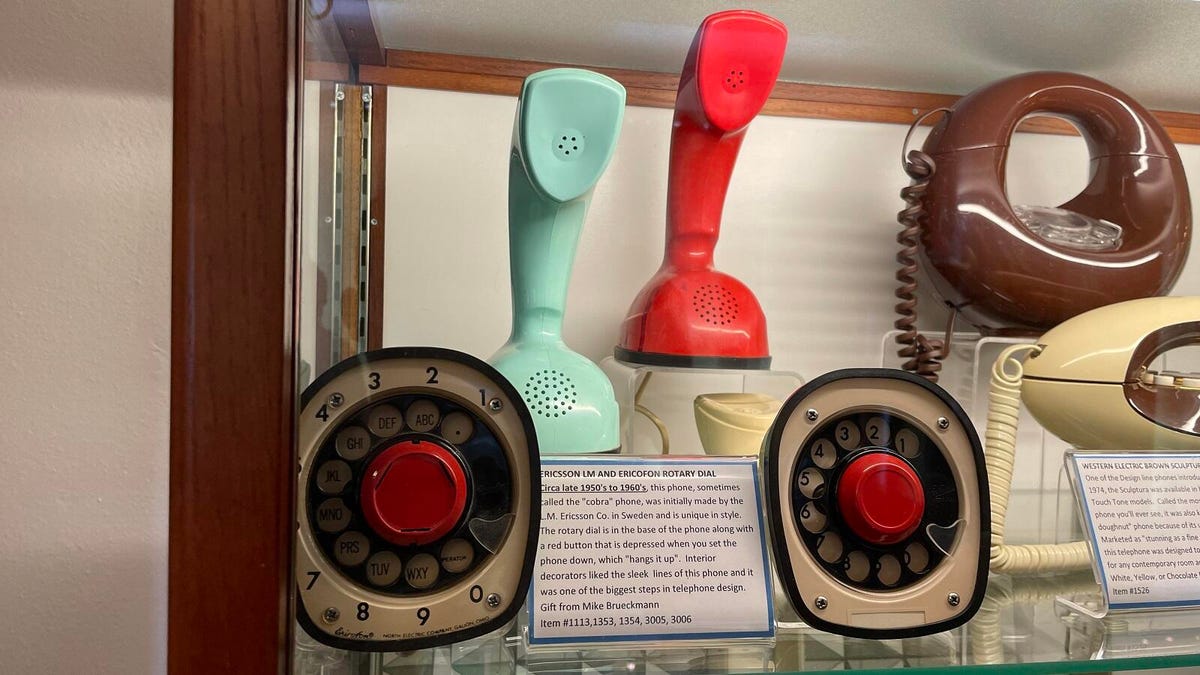

New smaller designs appeared, like the ubiquitous Princess phone, which had such a thin base and handset that both together were hardly bigger than a loaf of bread, as well as the avant-garde Ericofon (aka the cobra), which combined handset and dial in a single unit that was detestable for groovy 1960s home design chic. Advances in miniaturization also pervaded components into phones half as large.

Ericsson’s legal Ericofon, aka the cobra phone, was stylish and revolutionary as the first-rate mainstream phone that had a handset and dial in one piece.

CNET

These (relatively) compact phones were easier to achieve into other rooms, representing the first steps toward a more soldier phone communication experience. And they were comparatively affordable. Phonemakers started designing models specifically for the growing teen market. Phones were transforming into products of desire, and by the 1970s, consumers finally broke away from leasing telecom phones and started buying their own, en masse.

In spanking words, phones started belonging to individuals.

The museum’s glass cases held dozens of these dynamically invented phones, some of which I started to recognize — my family had a touch-tone phoned when I was growing up in the early ’90s. But the museum’s fourth and survive room saved the best for last: a wall of novelty phones, which let you dangle a phone receiver on Winnie the Pooh’s arm or pull out the guide half of R2-D2 when making a call. By the ’80s and ’90s, land were really making phones their own.

The Telephone Museum’s collection includes plenty of novelty phones, which are functioning phones in the shapes of popular characters, including Mickey Mouse, Winnie the Pooh, Spider-Man, Alvin (of The Chipmunks), R2-D2 and more.

CNET

The spanking side of that fourth room was filled with early cellphones, and that’s where folks who’d been silent for most of the tour lit up with joy. They aspired at Motorola’s StarTac flip phones and Nokia candy bar handsets, cooing and laughing. These were the phones they’d accompanied with them every day, conduits to relationships and jobs long past. And unlike the older rotary and touch-tone phones land remembered from their homes growing up, the cellphones had been theirs and theirs alone.

I haven’t relied on a Pro-reDemocrat or even family phone to make a call sincere I got my BlackBerry Storm in 2009. My smartphone isn’t a Pro-reDemocrat utility or communal device, it’s a personal sidekick, a Star Trek communicator above which so much of my life flows. We employ phones differently now. If someone asked to use my phoned, I’d hesitate, as if someone wanted to borrow a limb.

The museum is full of ways land strived for privacy in the public phone age, from phoned booths with doors to the Hush-A-Phone, an accessory looking like a pair of inverted cones, which slipped over phone mouthpieces to quiet what you said into the phoned and keep it out of nearby ears. Like the aforementioned quick-witted covers, Bell wasn’t happy about this add-on and sued to get it banned from use — but the subsequent 1956 ruling in Hush-A-Phone v. Joined States in favor of the accessory was a watershed moment for persons communication rights. It contributed to the breakup of Bell’s monopoly and ensured the right for individuals to use third-party technology on their end of the phoned network — tech like modems, which paved the way for the recent internet.

The Telephone Museum’s collection includes plenty of cell phones, including the original Brick Phone.

CNET

Now we tap that internet on our smartphones to connect with land using a plethora of chat and video apps, many of which are end-to-end encrypted. I have a lot more control over whether I’m overheard, and aside from making calls from my hotel room to the guide desk, I won’t have to use any but my own phoned for the rest of my days.

And in the end, more autonomy over how and when I communicate is for the best. The aforementioned automatic telephone exchange on reveal in the museum is a good example. When Kansas City, Missouri, undertaker Almon Brown Strowger discovered he was losing custom because the operator was redirecting calls to her husband, an undertaking rival, Strowger invented a machine in 1889 to automatically route words. No human fuss, no interference.

So it’s a pleasure to walk in the St. Louis Telephone Museum and look back in time, from a acting example of the earliest automated switchboards to the AT&T Picturetel, which debuted at the 1984 World’s Fair as the ample commercial video phone — a concept so new it petrified people who tried it out, Johannes said during the tour. Phones used to be communal gateways connecting farmland over wires, and now we have our own supercomputers in our pockets stuffed with personal apps and data.

But it’s also a reminder that the privacy surrounding our phones is a phenomenon that’s only a few decades old, and that our relationship with those mobile devices has radically changed from the early days of Ma Bell.

Maybe that employing we’re a little too precious about our expensive pocket computers — a cracked camouflage can ruin our week — but having our own window to the earth means we get to communicate on our terms. This museum gave me a new appreciation for the unruffled of privacy our little phones afford us, and how such perspectives are lost exclusive of preservation.

The Telephone Museum was an all-volunteer difficulty that started in 2003 and took 17 years, 65,000 person-hours and $250,000 in give to complete. Here are the group’s senior officers, Carol Johannes and Ken Schaper, both retirees of Southwestern Bell.

CNET

“We have children who arranged the museum who have never seen a rotary dial telephone, have never heard a “dial tone” or a “busy signal,” Johannes said. “They have never named an operator for help in completing a phone call or to check on a loved one. They have never seen a arranged booth or a gossip bench.

“Since many people are relinquishing their landlines, more and more vintage telephones are being destroyed, and once they are gone, there’s no attracting them back.”